Friends of Fintry Provincial Park

Greetings all,

As we start into another chilly month with gardens, trees and animals going into hibernation we should probably pay heed and follow suit in order to stay safe and healthy these next few months.

The lower floor of the Fintry Manor House is already in hibernation, but our Caretaker’s suite upstairs now has a couple installed who will look after things this winter. They look after another Provincial Park during the summer months so are used to the isolation and the responsibilities that go along with looking after an older building.

Despite our late start this year and with not being able to hold our usual three Fairs, we still managed to keep our heads above water. Our merchandise sales were good, entry donations were excellent and with being able to hire two students, our days open were more than when we operate only with volunteers. Membership was the one thing that took a hit this year as many people generally sign up or renew at the Fairs. Anyone who would like to renew or become a member and support all things Fintry can do so through our website www.fintry.ca. Fingers crossed that next year will be more “normal” …..Covid depending!

Following is another very interesting article by our very own historian Paul Koroscil….

Who knew that we had such a renowned architect creating these heritage buildings right here on the Fintry delta!

Stay safe everyone,

Kathy Drew

Friends of Fintry Provincial Park

James Cameron Dun-Waters’ Architect: J.J. Honeyman

By Paul Koroscil

J.J. Honeyman was born in Glasgow on April 9th, 1864. After architectural studies at Heidelberg University, Germany he returned to Glasgow in 1883 to article with Hugh and David Barclay rather than with his architect uncle, John Honeyman (1831-1914). Just a side note on John Honeyman. In 1888 he went into partnership with John Keppie (1862-1945). One of the draftsmen in their office was Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) who became Scotland’s most celebrated architect and designer of the 20th century. He was also known as an outstanding water colourist and artist. When John Honeyman retired in 1904, Mackintosh went into partnership with Keppie.

His first major commission was the Glasgow School of Art constructed between 1896-1909. It has been described as a Mackintosh masterpiece and his greatest design. I visited the School before the first fire in 2014. Unfortunately, a second fire occurred in June of 2018. However, there are plans to rebuild the School from original blueprints and it is estimated that it will take seven years to complete the rebuild.

On another occasion in Scotland my V.B.F (Maureen Montfort Selwood) and I visited Mackintosh’s Hill House in Helensburgh. The National Trust for Scotland acquired the House in 1982 as it was considered to be the finest example of domestic architecture by Rennie. The House was built between 1902-1904 for Walter Blackie and his family who owned a publishing business that ran from 1809 to 1991. The House is located in one of the wettest parts of Scotland and is situated on a “hill” overlooking the Clyde estuary. To cover the outside of the House, Rennie decided to use a new type of material, Portland cement. The result is that since its construction there have been major problems with dampness. To solve the problem, the National Trust commissioned architects, Camody Groarke to design and construct a chainmail “box”. Rachel Thompson, visitor services manager describes the “box” as “an amazing 165 tonnes of steel and 8.3 tonnes of chainmail mesh which makes up the “box” that now surrounds the House.” The “box” allows natural light to flood into the House, while encouraging it to dry out after decades of water damage. If you are in Helensburgh and you have a chance to visit the Hill House you will today encounter the “box”.

Now back to J.J. Honeyman. In 1889 he emigrated to Canada, crossed the continent on the C.P.R. and landed in Vancouver. Shortly thereafter he made his way to Vancouver Island and ranched with John Baird on Ployart’s Swamp near Black Creek in the Comox Valley. In 1891, Honeyman established his architectural practice in Nanaimo, first for a year in partnership with F.T. Gregg and then afterwards on his own. On January 12, 1892 in Nanaimo, Honeyman married Mabel Dempster, also a Scottish immigrant. They settled on a ranch called “Tarara” and commenced their family, which eventually numbered four daughters and one son. Honeyman enjoyed rugby and considered himself both a Conservative and a Presbyterian. He was a modest man; when asked if he could provide examples of his professional competence, he replied “I really don’t know. You might ask one of my clients.” Honeyman’s commissions at this time included the A.R. Johnstone block in Nanaimo, 1893, a school in Cumberland, 1895 and Nanaimo Central School 1895-96.

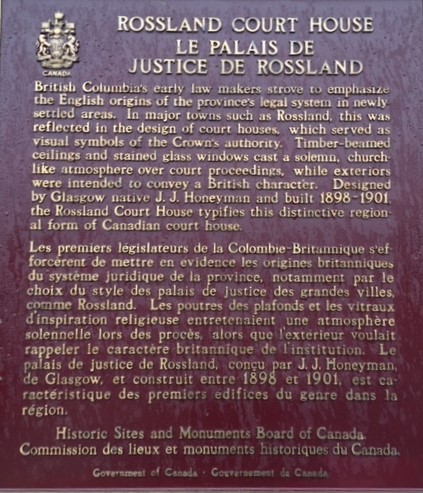

In 1897, Honeyman moved to Rossland where his largest and best-known individual project was the Rossland Court House. Walking up to the front of the Court House, which is located on Columbia Avenue at the corner of Monte Christo Street on a rise above the downtown core, one has a feeling that this massive, dominant structure certainly symbolizes a deep respect for the rule of law and the English origins of the provincial legal system. The historical significance of the building has been exemplified by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada by designating the Court House a National Historic site and recognizing J.J. Honeyman as the architect. (See wall plaque on front entrance of the building).

The Court House was designed in 1898 but not completed until 1901 as a result of the first contractor’s inability to carry out the task. By the time of completion, the building’s cost rose from $38,500 to $58,122 proving that public works cost overruns are by no means new in British Columbia. The edifice featured a symmetrical front facade, corner towers with steep bell-cast roofs and an arched entry and window openings. Pinkish-tan brick cladding was used above the base of local dark granite.

The main court room features an open timber roof, cedar paneling and stained glass windows by Henry Bloomfield and Sons, bearing the provincial arms and those of Sir James Douglas, the province’s first governor, and Sir Matthew Baillie Begbie, British Columbia’s first judge and subsequent Chief Justice.

In the present era one of the platforms promoted by political parties at the Federal, Provincial and local governments and various Societies is reconciliation. One of the debatable current actions of promoting reconciliation is the removal of statues of prominent Canadian leaders who, during their time carried out an injustice. An example of this action took place in 2020 when the Law Society of B.C. approved the removal of the Begbie statue from the Law Society foyer.

In a letter to the editor of the Vancouver Sun, (September 12, 2020) Craig Ferris, President, Law Society of British Columbia, explained the rationale for the decision the benchers made for the removal of the Begbie statue from the Law Society foyer. He indicated that it was because the necessary work of the Law Society in addressing reconciliation, was hindered by the prominence of a statue that made an important segment of the public feel unwelcome when visiting our offices. He emphasized that the Law Society must be an open and inclusive environment in order to do its job on protecting the public interest in the administration of justice for all. The debate about the historical legacy of Chief Justice Begbie reflects the different views about the man and his work, but, the debate should not impede the Law Society from being open and able to fulfil its mandate to protect the interests of all the public. I wonder, did the Law Society miss the stain glass window in the Rossland Court House and other Court Houses constructed during that era; for example, the Fernie Court House and if so, are they going to remove the Begbie windows?

While in Rossland, Honeyman also designed a number of residential properties, for example a home for his wife’s brother Charles Dempster. Also, it is probable that Honeyman met George D. Curtis who would eventually become an architectural partner. Curtis was born in Ireland on August 1, 1868; his family had been officers in the Royal Navy for generations. He studied at London’s Finsbury Technical College from 1884-85 and for the next three years he articled with a London firm. In 1889 he emigrated to Canada taking up survey work in the 1890’s. The C.P.R. had built a branch line to Nelson, which had become an important West Kootenay mining supply centre and by 1897 Curtis opened an architectural office there. He undertook various commercial, religious, residential and public commissions in Nelson, Rossland and Greenwood. His projects in Nelson included St. Saviour’s Anglican Church, (1898-1900), a good example of a Gothic English perpendicular parish church, while his Cathedral of Mary Immaculate, (1898-99) is a mature example of Roman Classicism, favoured by the Catholic Church in Canada at the time. In Greenwood, Curtis designed the City Hall, built in 1902-3 as the provincial government building and courthouse and a public school.

As they crossed paths in the Kootenays, they both decided that there was a greater business opportunity on the coast. They both decided to move to Vancouver and in 1902 they established their architectural partnership. In Vancouver their firm established itself as one of the most prominent and prolific firms in the city. They were responsible for a number of churches, public buildings, private residences, apartment buildings, industrial structures and banks.

Honeyman and Curtis undertook a number of projects for the C.P.R. Curtis took over the supervision of the original portion of the Empress Hotel in Victoria when Francis Rattenbury (at the time the most recognized architect in B.C.) resigned in 1906, and continued to supervise the ongoing expansion programme, 1909-1914, that included two new wings and the Crystal Ballroom, all designed by W.S. Painter. In 1911 they designed an addition to the Hotel Vancouver for the C.P.R. Corporate clients included the Bank of Montreal, for whom they designed a stone-clad Temple Bank at Main and Hastings, built 1929-30, that marked the end of the local use of classicism. Its columned entrance, pedimented doorway and sculpted heraldry were intended to invoke confidence and a timeless sense of stability. Also, they were responsible for the building of two other Bank of Montreal structures, one on Main Street at East Broadway, 1929, and another on Main Street near Prior Street, 1929.

Another of Honeyman and Curtis’s landmark projects was the Vancouver Fire Hall No.6, 1907-09, located in the West End. At the time of its construction it was the “only fire hall in the world completely equipped with Auto Engines”. This brick and stone building has a metal tile roof and strong horizontal emphasis, contrasted with a vertical hose tower. The partnership also received a number of church commissions. St. John’s Presbyterian, 1909, in the West End was an impressive stone Gothic Revival structure with a tall corner turret. The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1925, in North Vancouver reflected Christian Sciences’s preference for classically inspired forms. Another notable church was Shaughnessy Heights United Church, built in 1928-30; a beautifully proportioned stone-faced structure reminiscent of a traditional English parish church.

Most of their initial residential commissions were in Vancouver’s West End. From 1912 until 1929 their domestic work was located in Shaughnessy Heights, Point Grey and North Vancouver. For Matthew Sergius Logan, lumberman and Parks Commissioner and advocate of the Stanley Park sea wall, they designed a grand Craftsman-style home on Point Grey Road, 1909-10. The Shaughnessy home of industrial supplier, Bryce W. Fleck, 1929, in the Tudor Revival style, includes bay windows, stained glass and curved gable above the entrance.

The firm’s prosperity, allowed the partners to build their own substantial homes and establish vacation properties for their families. In 1908 Curtis cleared land outside Comox and in 1912 built a small cottage; this property is still owned by the Curtis family. In 1913 Honeyman built his own home in Kerrisdale, which he called Kildavaig after a Scottish home in which he had once lived. By this time, Kerrisdale had become a desirable location, “Just far enough from the noise and bustle of the city for peace and contentment”. Kildavaig stands in excellent condition today. In 1929 he also built a cottage at Hood Point on Bowen Island, used by succeeding generations of his family.

The one commission outside the Lower Mainland that Honeyman undertook was related to his life-long Scottish friend James Cameron Dun-Waters. He would design and construct a house and a barn on Dun-Waters’ Fintry property. The design of the Manor House in 1911 was a sprawling Tudor Revival house. This first house burned down during renovations in 1924. He designed a second house to replace it, with rich materials and spaces, including gracious verandahs. Of particular interest was Dun-Waters’ trophy room, with trophy heads hung on the walls and the construction of a separate cave where his prize Kodiak bear would stand on moss-covered boulders; with a waterfall flowing down the rocks and disappearing under the floor inside the cave off the trophy room. I wonder, did Dun-Waters come up with the idea of a cave to display his prize trophy or did Honeyman? I think I will go with Dun-Waters. In National Trust estates in England and in Scottish Trust estates I certainly have come across trophy heads on the walls in some estates but I have never come across a cave designed within a trophy room to house a prize trophy.

To house Dun-Waters’ Ayrshire cattle, Honeyman designed and constructed a barn. Honeyman decided to build a polygonal barn, (usually more than four angles and sides) and the architectural pattern he chose was an Octagon (eight angles and sides). The octagonal design appears to have its origin in ecclesiastical structures. In 1970 archaeologists found the remains of an octagonal Romano-Celtic temple, dated AD325 in Chelmsford, Essex. Almost five hundred years later, probably one of the finest built octagonal structures built, is Charlemagne’s palace chapel, (now the cathedral) at Aachen (now Germany).

One of the outstanding examples in England is located in the mediaeval village of Pembridge, Herefordshire. Beside the Church of St. Mary the Virgin stands the Bell Tower, a separate building with an octagonal design. The structure dates from the early 13th century though only the four huge timber corner posts remain from the original building. It was restored in 1898 and 1957. On entering the belfry with its massive wooden beams, I had the eerie feeling that reminded me of standing in the middle of the Fintry barn. Structurally, the octagonal Bell Tower is related to the wooden stave churches of Norway. The irony of this comment for me relates to my sabbatical at the University of Oslo where on a weekend venture with my V.B.F. we came across one of these magnificent octagonal stave churches.

In the 18th century, polygonal buildings experienced a revival however, not in ecclesiastical buildings but in farm buildings, particularly “cow houses”. As a result of agrarian reforms in Britain new innovations in farming led to the development of new model farm buildings. One such building was the “cow house” constructed in direct response to the wintering of cattle. Most of the “cow houses” in the beginning had an interior design which was circular, octagonal or hexagonal in form. Also, architects argued that these types of structures provided the most efficient use of space for the smallest amount of material. However, they had less appeal to the average farmer who found the design too complex and the initial construction costs higher than average. Despite these costs they became very popular with architects between 1800 and 1937. At this time there were more than 30 pattern books published devoted to farm buildings in Britain.

Capitalizing on the success of British architects the idea of polygonal barns diffused to North America and flourished throughout the 19th century. In the United States numerous polygonal barns were built in New England and the Mid-Eastern States. In the 1880’s the idea of polygonal barns diffused across the border and began to appear in Eastern Canada and then across the Prairies to British Columbia. In 1995, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada commissioned a survey of polygonal barns constructed between 1888 and 1925. For British Columbia the study indicated that there was only one octagonal barn. It was located at 7071 No. 9 Road in East Richmond. It was known as the Ewan Cattle Barn, a 12-sided structure measuring 50 ft high and 100 ft in diameter and built of local red cedar. Alexander Ewan was born in Aberdeen, Scotland and emigrated to B.C. in 1864. Economically, he became involved in the fishing and agricultural industries. He built one of the largest canneries on the Fraser River and in 1893 on his 640 acre farm, he constructed his octagonal barn to house and feed up to 100 head of cattle. The inventory seems to have missed the Dun-Waters’ Fintry octagonal barn. When Dun-Waters commissioned Honeyman to build a barn, Honeyman must have known of the popularity of polygonal barns and particularly those using the octagonal pattern. In fact, the Crown Lumber Company, 1900-1915, advertised an Octagonal Pattern No. 3381 plan of a ready-made (today prefabricated) polygonal barn.

Honeyman’s Fintry barn contains 2,784 square feet including the silo area. It sits on a 20-inch high concrete foundation, and the floor area and feeding troughs are also constructed of concrete. Each of the 15 stalls contains a stanchion and there are three milking pens and a calf pen. The exterior of the barn is covered in fir board and batten. Undoubtedly, Dun-Waters was quite pleased to have such a distinctive barn to service his initial herd of 17 pedigree Ayrshires. Also, the cattle must have been pleased! Over the next few years, Dun-Waters expanded the herd and by 1931 he had 130 Ayrshires, probably one of the largest herds in Western Canada. On your next trip to Fintry do not miss taking a tour of the magnificent Fintry barn.

For Honeyman and Curtis the numerous commissions of the 1920’s fell off dramatically at the beginning of the Depression. Along with others in their profession, their partnership was devastated by the Great Depression, and they both retired by 1931. Honeyman died at home in Vancouver on February 18, 1934. Curtis, in ill health, retired to Comox in 1931 and died there on September 8th, 1940. Honeyman certainly had an interesting architectural career and I hope you enjoyed the script.

Just a final thought. Since Honeyman is recognized by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in Rossland, the Fintry Board of Directors might want to consider a plaque recognizing his work on Fintry’s unique Octagonal Barn and the Manor House!

The photos of the Rossland Court House were taken by my V.B.F.